Originally published on East City Art, November 11, 2019. By Miguel Resendiz.

In 1989, the Corcoran Gallery of Art cancelled a major retrospective of Robert Mapplethorpe’s work titled A Perfect Moment: Photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe. The main reasons for this cancellation were the inclusion of Mapplethorpe’s photographs containing homoerotic imagery and two images of nude children. The show and its cancellation caused quite a controversy, inspiring protests from within and beyond the Corcoran. Regardless of its content, the show seems to have become a symbol for the fight against institutional censorship. This past summer, thirty years after the cancellation, the Corcoran—now a part of George Washington University—installed 6.13.89, an archival exhibit reflecting on these decisions, through which it cemented this event’s status as an important moment in queer and Washington, DC history.

Gallery 102, another art gallery at the university, recently organized From the Margins, as yet another response to this anniversary. The title is a nod to bell hooks’ book Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (1984) which describes how black women were on the margins of contemporaneous feminist theory.[1] In Gallery 102, however, queer people occupy those margins. The show consists mostly of photographs by queer artists and addresses issues in queer representation, identity, and the act of critique. Spanning five decades, the earliest work in this show dates from 1979, but most of the art was created this year.

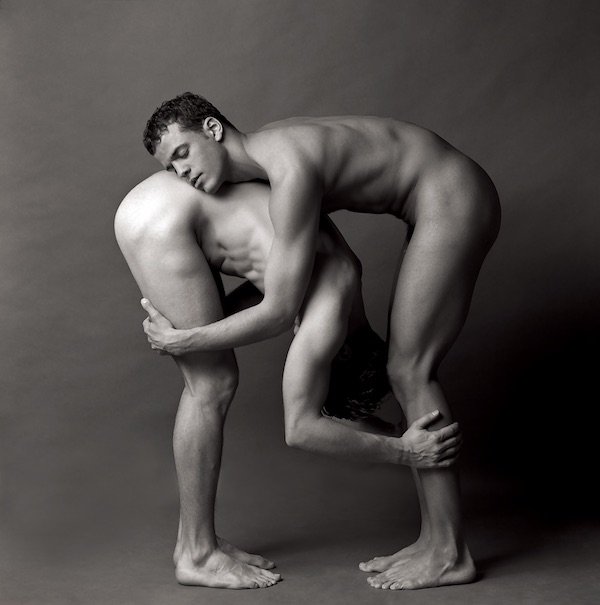

In keeping with the risqué content of the cancelled Mapplethorpe exhibit, many of the photographs in From the Margins contain homoerotic imagery. The viewer becomes forced voyeur watching Peter Clough’s 93-minute video Blow Job—which depicts just that. Unlike Andy Warhol’s 1964 video with the same title, which only shows the head and expressions of a man supposedly receiving fellatio, Clough’s work focuses on the artist’s head as he performs the act on a male; full genitalia are on display. If one can tolerate the initial embarrassment of watching the video (the screening is in a dark room), one might eventually realize that the slow-motion capture of this sexual act turns it into an intimate scene. The primary goal does not seem to be the arousal of the viewer; rather, the video plainly captures two male bodies in the act of pleasure, thereby towing the line between pornography and documentary.

John Paradiso, Proceed with Caution (detail), 2019. Mixed media, inkjet print on cotton fabric, acrylic, and varnish on wood panels. 52” x 52” x 1”. Courtesy of John Paradiso.

John Paradiso’s Proceed with Caution is a 25-panel mixed media work. Each panel holds a photograph of two shirtless men kissing—clipped from various erotica—which is framed by printed images of pansies and yellow caution tape against a pink background. The bright palette and flowers give the work an attractive quality. Pansies and caution tape are a recurring motif in the artist’s oeuvre. “Pansy” is a derogatory term for queer men—an association the artist is clearly trying to remediate.[2] Here, the word “caution” can be read not only as a reference to the “explicit content” warning page at the entrance of an adult website, but it can also refer to the past and present dangers of expressing non-heteronormative love. Removed from their explicit contexts, the images become somewhat impotent. What could be so dangerous about two men kissing? Their power comes from their collective presence. The 25 images in this work are reproduced in an area greater than 4’x 4’. Their teeming reproduction attempts to normalize and center these marginalized activities.

Unfortunately, most of the artists presented in this exhibit are men, evidence that the patriarchy persists even within the margins. However, Naima Green’s work Pur·suit is positioned across from Paradiso’s panels, where it acts as a counter to this male-centricity. Pur·suit, is a deck of playing cards that carry images of queer women, trans, non-binary, and gender nonconforming people.[3] The artwork illuminates the need for representation of marginalized groups (even in queer spaces), and there is no better medium than a deck of playing cards for the purposes of mass reproduction and distribution of images of people who lack visibility. Many of the people represented are smiling and are shown as their best selves. Strictly in terms of numbers, this work contains the largest quantity of images of people who do not identify as men in this exhibition. Yet, it is also the smallest work in the gallery space, each card being 3.5” x 2.5”, and it is relegated to the farthest corner of the exhibit. Greene is one of only two women artists in this show. Further attempts to diversify the artist pool are evident in the “Resource Wall” that displays Do-It-Yourself publications by a broad array of artists.

Naima Green, Pur·suit, 2019. Deck of playing cards. 3.5” x 2.5”. Courtesy of Naima Green.

A series of essays in the accompanying exhibition catalog acknowledge and grapple with this lack of diversity in the exhibit. They each outline some of the difficulties with the notion of critique and the idea of inclusive representation. On the one hand, labeling artists by their intersectional identities (e.g., White, Black, Asian, queer, gay, lesbian, asexual, cisgender, transgender, agender, disabled, etc.) allows us to see who is included and excluded in our dialogues. On the other hand, using labels as a measure of diversity carries the risk of tokenization, wherein the act of inclusion becomes a process of checking off boxes on a list. Further, these labels may sustain the process of othering or marginalizing people who fall outside of the “center.” Labels are at once liberating and confining, in that they allow people to make sense of who they are, and yet they also carry enormous baggage from their associated histories and standards. Keeping up with these ramifications can be exhausting.[4]

The Language Must Not Sweat is a photograph of the back of a black man’s head lying on a table. The figure’s clean-shaven scalp is covered in beads of sweat as it carries the weight of 11 books with titles like Scripting the Black Masculine Body, On Being a Black Man in America, and Hung. The work perfectly encapsulates many of the issues at stake in a show like this.

Shikeith, The Language Must Not Sweat, 2018. Photograph. 20 x 30 inches. Courtesy of Shikeith.

From the Margins simply asserts that there are in fact margins and that the perspectives within these margins are in no way cohesive and can often oppose one another. As bell hooks wrote in 1989, “I was not speaking of a marginality one wishes to lose…but rather as a site one stays in, clings to even because it nourishes one’s capacity to resist. It offers to one the possibility of radical perspective from which to see and create, to imagine alternatives, new worlds.”[5] At the core of this dialogue is the fundamental question: When are the marginalized free to just be

From the Margins is on view through November 15, 2019 at Gallery 102, 500 17th Street, NW

Washington, D.C. 20006. Open Monday – Friday, 9 AM – 5PM.

[1] The exhibition catalog mentions this association: Gallery 102, From the Margins: A Field Guide to Critique, Edited by Andy Johnson et al. (Washington, DC: Gallery 102, 2019), Exhibition Catalog, 5.

[2] See Eric Hope’s take on an earlier work by John Paradiso here: https://www.eastcityart.com/reviews/east-city-art-reviews-new-arrivals-2015-at-the-university-of-maryland-stamp-gallery/

[3] Product description on the artwork: Naima Green, Pur·suit, 2019

[4] Many of these ideas are articulated in bell hooks’ writing. For example, bell hooks, Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, 1984.

[5] bell hooks, “Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness,” In Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, no. 36 (1989), 20. http://www.jstor.org.proxy-um.researchport.umd.edu/stable/44111660.