Originally posted on GWToday. By Greg Varner.

Certain questions come up repeatedly in Alexander Dumbadze’s George Washington University course on Later Twentieth-Century Art, including: What is a work of art? Who can be an artist?

Beginning with post-World War II art and reaching through 2001 and the terror attacks of 9/11, Dumbadze, associate professor of art history in the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences’ Corcoran School of the Arts and Design, leads students through a tumultuous half-century, focusing mostly on North American art and artists.

The question of who can be an artist leads to a consideration of “the various levels of discrimination that have historically kept people out,” Dumbadze said, which naturally connects to “the politics of being an artist and the ways in which identity and subjectivity are represented and constructed.”

In the postwar period, artists were portrayed differently in popular media depending on their gender. Photographs of Jackson Pollock would often depict him in action, bending or kneeling over a canvas to make one of his famous drip paintings, while a woman such as Helen Frankenthaler would likely be pictured in a contemplative pose, perhaps standing in front of an artwork with a smudge of pigment on her smock.

Stretching from Abstract Expressionism and the New York School to Pop and Conceptualism, through Land Art, Postmodernism, art in the age of AIDS and in the age of terror, Dumbadze’s course examines these and other movements and topics, relating artworks to each decade’s wider events, themes and occurrences.

“I want students to become more aware of their own subject position, their own points of view, their own place in the world,” Dumbadze said, “and more aware of the types of things that are affecting them—and how that is also going to affect the way they view the past.”

The course attracts a variety of students, including art history majors and minors as well as studio art students and students from CCAS, the Elliott School and elsewhere.

“One of the best parts about teaching courses like this is getting students from all over the university,” Dumbadze said. “That creates a great classroom environment where you have different types of perspectives.”

Visit to the 1960s

In a recent class session, Dumbadze focused on Land Art and the environmental movement that began to surge in the late 1960s. He began by reviewing the previous week’s lesson on conceptual art, which he believes is essential to understanding contemporary art as a whole.

“Conceptual art makes it possible for art to engage with politics in ways it couldn’t before,” Dumbadze said. “It’s the difference between representing politics and actually embodying politics.”

Ideas are given preeminence in conceptual artworks, he said—which is not to suggest that a painting or sculpture is all feeling or expression, without ideas. But the medium no longer dictates the problem, as paint and clay once did.

“Conceptualism opens up the idea that anything could be art,” Dumbadze said. One of several examples he cites is Chris Burden’s “Bed Piece” (1970), for which the artist turned himself into an object and stayed in bed for 22 days in an art gallery. Such work highlights the instability of the line between subjectivity and objectivity.

“When the person becomes the work, it’s harder to talk about,” Dumbadze said. “That makes criticism and art history all the more complicated.”

The 1960s, Dumbadze reminded the class, were a period of upheaval. Just as boundaries were expanded and tested in music, fashion, politics and other areas, they were pushed in art. Major conceptual shifts were taking place in the way we experience land, time and space. Partly impelled by the changes wrought by technological development, questions naturally arose: How far can you go before reaching the boundary? Is there a boundary?

With space travel and the technologically driven power to see farther away and deeper within, the human sense of scale was altered. The new frames of reference, along with the Cold War and the threat of nuclear weapons, could make individuals feel infinitesimal.

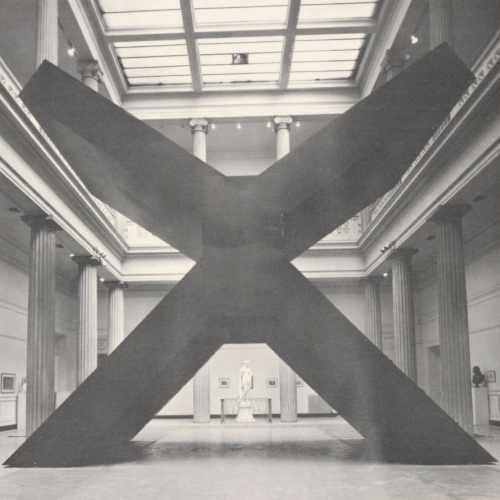

A sculpture fundamentally about scale was exhibited in the 1967 exhibition “Scale as Content” at the Corcoran Gallery. “The X” by Ronald Bladen is a monumental form of painted aluminum. Reaching to a height of 22 feet, it stood imposingly in the Flagg Building’s atrium.

Whereas artists had previously been heroic figures lodged mainly in the studio, they now moved outdoors and into surprising places, not just galleries and museums. Art could be ephemeral, no longer aiming for the illusion of permanence. Earth itself could be carved, incised or shaped in other ways, as in Robert Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty” (1970), one of the most famous works of land art.

“Spiral Jetty,” in a remote area of Utah, is not readily accessible; like many works of land art, it is most often experienced in writing, photography and film rather than in person. Whereas artworks are often discussed without reference to their construction, Smithson wanted his ideas and process to be foregrounded. The construction of the jetty with earth-moving equipment is shown in a film which also highlights the thought that went into the work.

“It’s a sculpture, a thing, an image,” Dumbadze said, “but it’s not about the environment.” Not all earth art was responding to environmental concerns, in other words, though the looming awareness of environmental disaster affected many artists. Some of the other figures discussed in the lesson on environmental art include Michael Heizer, Nancy Holt and Bonnie Ora Sherk.

Working with organizer Jack Wickert in 1974, Sherk founded “The Farm” in San Francisco, simultaneously a community center and garden, a work of “environmental sculpture” and a performance that lasted 13 years.

A big, noisy conversation

Kylie Weisberg is a sophomore majoring in political science who realized while taking a previous art history course that something had been missing in her education. “I needed a creative outlet,” she said, “so taking this course helped me engage with that side of my brain and gave me a new way of learning. I’ve noticed in other courses I start thinking of things in a broader sense and my perspective is a little different.”

In Dumbadze’s class, Weisberg has especially enjoyed learning about feminist conceptual art and is particularly interested in the ways artist Rosalyn Drexler addresses gender stereotypes.

Her classmate Riley Buikema, a junior anthropology major, said the course has inspired a deeper appreciation for works of art.

“It started when we went to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and I went through the Yayoi Kusama exhibit,” Buikema said. “I had actually gone through that exhibit before, and I never really got it, but in class we talked about how her work reflected her identity as a female artist.”

A contemporary Japanese artist, Kusama is widely known for her “Infinity Mirror Rooms” and for her fascination with polka dots. Her influential work is on view at the Hirshhorn in the exhibit “One with Eternity,” a required destination for Dumbadze’s students.

“Kusama is a really interesting figure,” Dumbadze said, “because she has become a larger-than-life person both in the art world and beyond. She raises so many interesting questions and her work is also deeply existential and mystical.”

The questions raised by Kusama’s work are of great interest to Cristina Silva, a senior majoring in graphic design. Silva is intrigued by Kusama’s play with ideas of infinity and nothingness, and also how she enables viewers to celebrate themselves. “You’re contributing to the art,” Silva said. “You’re a part of it.”

She praises Dumbadze for his openness to the response of his students to the works they are studying. “He makes us really think about the art and our opinions about it rather than imposing his own opinions,” Silva said.

Dumbadze said he doesn’t mind if students say a work they are discussing is not art.

“I say, ‘Great! I want you to tell me why.’ I think it is totally valid for students to not like something,” he said. “To be able to vocalize discontent is really key—to debate and argue and wrestle with positions you don’t agree with.”

This ability is, in fact, fundamental to democracy, which has often been likened to a big, noisy conversation. Dumbadze has sometimes changed his own opinions in response to a spirited class discussion. Teaching is a two-way street, he said; he can help students see work in new ways, and the reverse also happens.

“It's something that comes alive through conversation in the classroom,” he said. “Works of art can be really compelling ways to think about life in the world, and there are many ways to approach different questions. In this class, we use artworks, and the ways in which artists are thinking about things, to pose questions about identity or representation or politics or all these things. Art can open up things that maybe other modes of thinking don't.”

After quoting Joan Didion’s famous line “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Dumbadze expressed his conviction that art historians have a responsibility to understand why some narratives are more compelling than others, to examine narratives from several sides and to articulate their multiplicities in their writing and teaching.

“I want students to work really hard, but in a pleasurable way,” he said. “I love when they walk out of class tired because they've been thinking and pushing themselves to be engaged with ideas and with what their classmates are saying.”